‘falling is the essence of a flower’

Yukio Mishima

REMEMBER TO DIE / MEMENTO MORI

The impulse to explore the shadowy unspeakable inevitability of the end of life ironically begins from the place of the birth of an artistic catalyst… a genesis if you will.

Living in the country as I do one is constantly reminded of the cycle of life as newborn lambs spring impossibly high in an abandoned, twisting dance of joy just to be alive while lying by the bordering track is a young bird who has met the end of life in a splay of feathered surrender.

My enquiry into impermanence began earlier than it is possible to cognitively recall and while recoiling at reminders of both fauna and flora death surrounding my young life it was not until I was ten that news of the death of my uncle who I had never met, in the U.K, came from my mother and prompted me to leave a small and serious note for my father at his place at the dinner table saying in tiny writing, as if to not quite be there: ‘Uncle Max is dead!’

Woman / Man / They have been alternately fascinated and repelled by this notion of death and where some cultures embrace and honour this mystical passage others hide it away under multiple seemingly impervious layers of denial and arms length refusal.

It is often the artists of all orders along with spiritual explorers who collide with this slippery examination of the messiness of death, of this existence or certainly of this body, this corporal clothing.

Painters, photographers, writers, choreographers, film makers, songwriters, sculptors, clowns and hybrid artists have all reached into the depths of the unknown to ask questions through their work about this riddle that defies a real knowing.

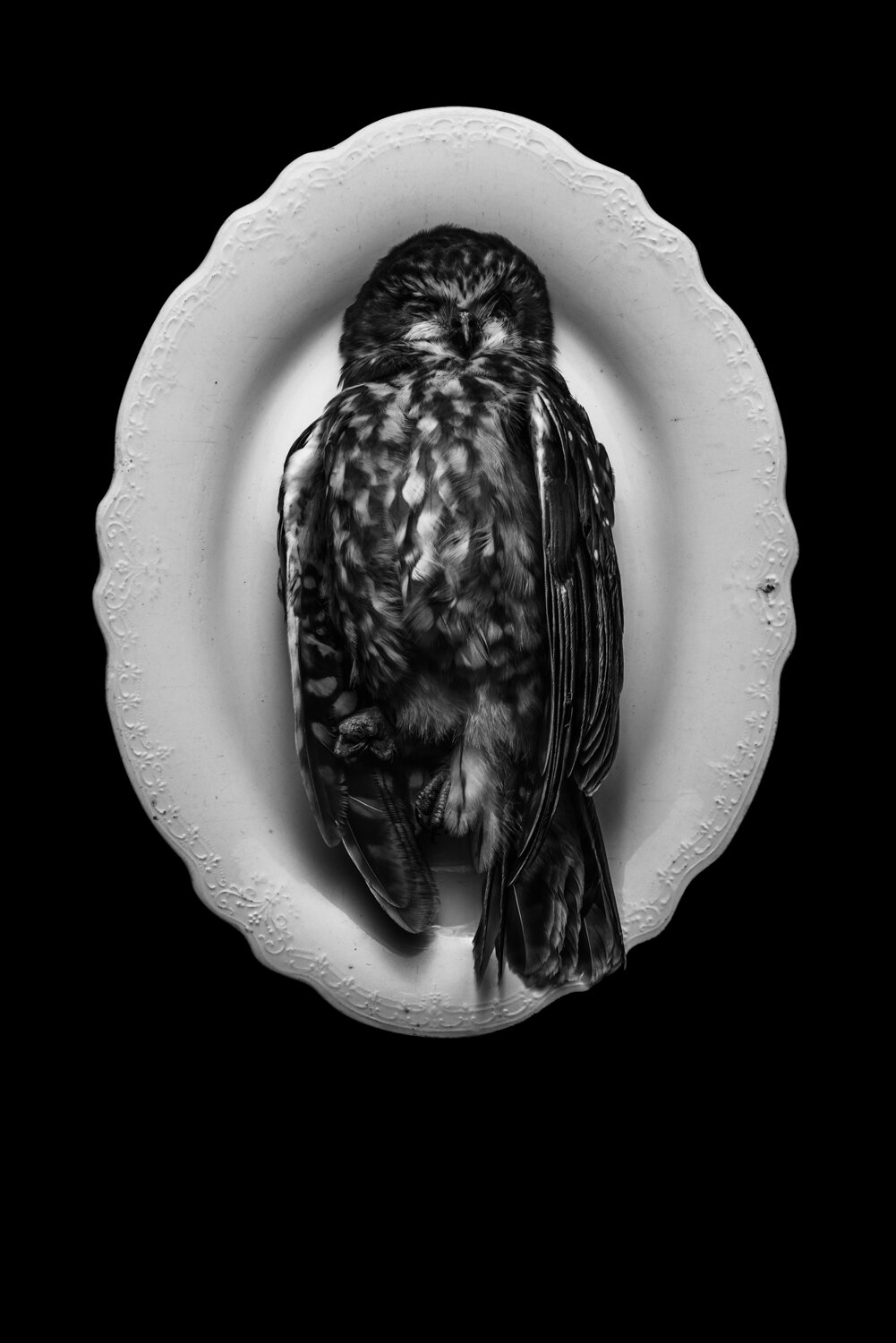

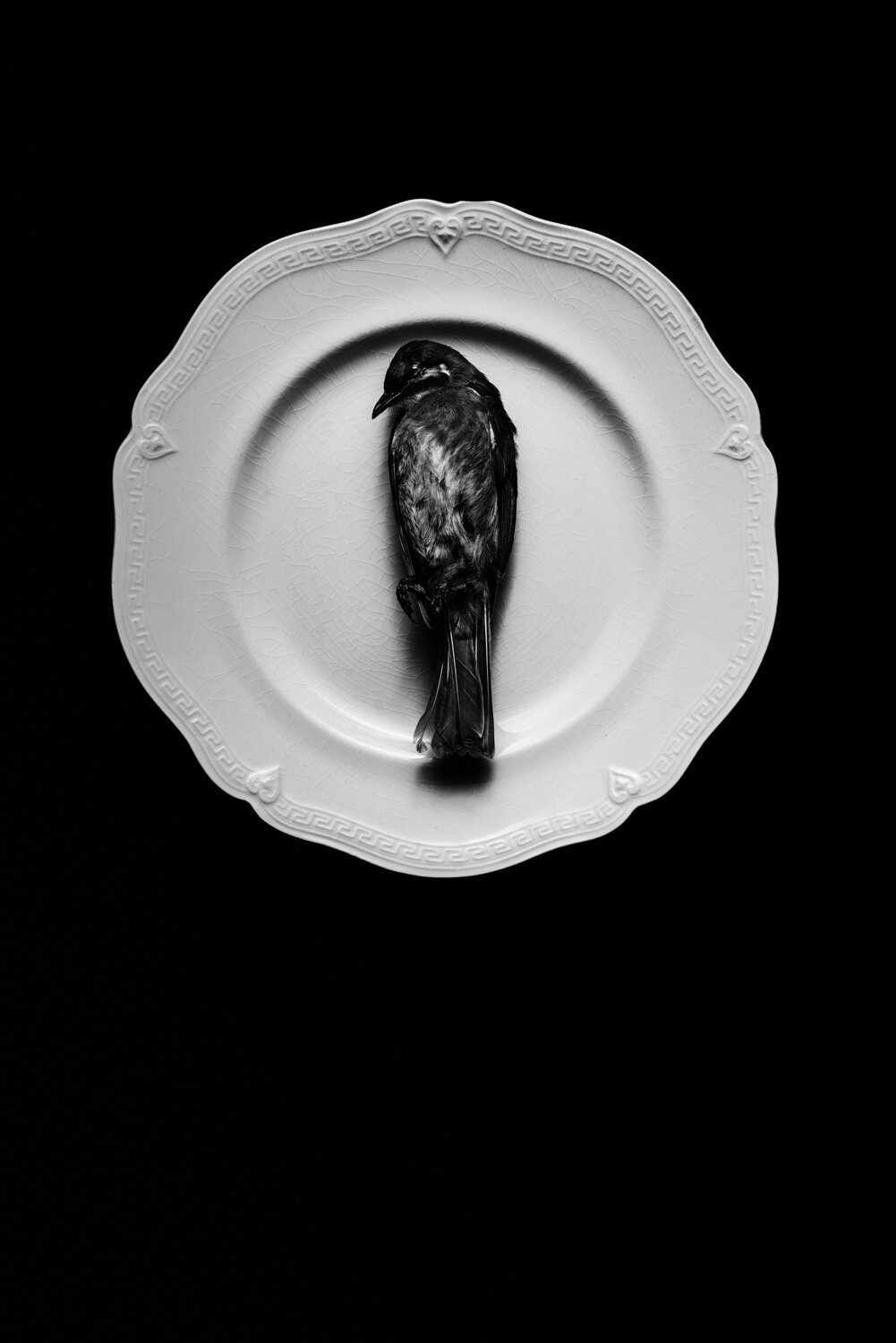

In the past year I have come across various beautiful birds who have departed their feathered costuming. A magpie hit and run found in the street, a perfectly formed finch in a pile of leaves in my garden, a bronze winged pigeon lifeless by a large shop window following its collision, a very young blackbird lying untouched but unalive on the road near my house and a raven found by new friends, also lifeless, on a back country road in all its magnificence. Friends carrying lifeless avian forms they have kept cold until we met each other for the gentle and remorseful hand over. I know there will be more to come.

And so, the photographers dilemma to preserve or to interpret, to capture something in this breathless form of bird that is a reminder of sorts.

Memento mori.

Don’t forget to die.

And so begins the effort of a new series of images that must include on some ephemeral level the intimacy of these departed flying souls who soar without feathers or wings to assist their soaring.

My decision to present them on old, beautiful platters somehow formalises the series and the enquiry in classic portrait form.

Post-mortem portraiture or memorial portraiture became de rigeur in Victorian times and due to the high percentage of infants and young children who succumbed to devastating illness such as typhoid, tuberculosis, cholera and other diseases we see so many poignant images of parents holding the child dressed in their best clothing or nightgowns posed as if still with the living.

These images were a precious reminder of the dearly departed and became a memorial often displayed in a place of pride, A shrine of sorts and perhaps also a reminder of the fragility of this lifespan.

Photographically given the slow exposure times of cameras, it is not uncommon to see that the living would be slightly blurred with the slight movement of the body when breathing while the post-mortem subject would be in complete inanimate focus.

This captured aspect of all portraits can suspend time and if a pose were held for periods of time any portrait could potentially appear to be either suffused with life or devoid of such life. How often have we seen candid photographs with the captured victim showing a rictus grin in an effort to present as full of life and perhaps artificially joyous in the presence of the ‘capture apparatus’?

This has begun to interest me and so I have embarked on a series of images beginning with birds who have passed on dressed in their fine feathers and preserved for a moment or suspended in time on a beautiful, yet static platter. My intention was to photograph the dissolving of these feathered bodies over time as a record of their beauty and of their impermanence.

The brilliant and sometimes accidentally controversial American photographer Sally Mann has a series ‘What Remains’ that while confronting in its examination of decaying bodies, is also haunting, beautiful and starkly rendered. Extraordinary images.

My real interest lies in the fine line between animation and the inanimate. Millions of people do the pilgrimage to Varanasi in India where the sacred river welcomes the ashes of the departed and this process of body to ashes can be seen as a sacred yet ordinary event alongside the life of the city. Although things have changed dramatically in recent times it is still considered indecent for journalists to show images of the dead in certain situations.

While I have no clear sense of where my own exploration is ultimately headed, I am lead here by feel. Each of the beautiful birds I am photographing at this stage have died naturally and so in some way this process of capture is an honouring of sorts perhaps even of the mystery of life itself and of the riddle surrounding the question ‘What is Life’?

Simon Dow, May 2021

all images © Simon Dow Photographer 2020 / 2021